Each of the workshops to this point have reminded participants that setting the tone early and clearly in the course term is vital for student participation. This workshop elaborated on that concept and went a step further by showing participants how we could include our students in helping to define and set standards for participation and classroom respect.

For this workshop we adopted many of the tips from Jocelyn A. Hollander’s 2002 paper, “Learning to Discuss: Strategies for Improving the Quality of Class Discussion” published in Teaching Sociology (v.30, pg.317-327). While the paper was written about a sociology course and published in a sociology journal, as a SCIENTIST who is planning on teaching biology as a career, I find Hollander’s techniques useful for my field too. The techniques are particularly useful for discussions that will inevitably arise from topics that are agreed upon in my field but not in mainstream America such as climate change and evolution.

The basics are this, 1) allow students a chance to identify characteristics of a good and a bad discussion - including what respectful discussion is like, 2) decide as a collective what discussion should be like for the term in your class, 3) have students reflect on how they’d like to participate at the beginning of the quarter, 4) have the students reflect midway or at the end of the quarter on how they actually participated and why they participated the way they did. This serves two purposes, it sets clear expectations and rules and allows the students to feel valued - thereby setting the tone and expectation that their participation is also valued.

We illustrated this technique in our workshop by collectively defining good and bad discussion, and having a conversation about respectful behavior.

During the discussion it was pointed out by the participants that respectful behavior can vary widely depending on background and culture. One participant noted that in her culture interrupting was very rude and that she had to adjust when she started her schooling in the States. Another participant noted that he was uncomfortable interrupting his students during discussion even when he felt a need to re-direct the discussion. He used the technique of raise your hand to start a new discussion, and raise one finger to reply to a topic. Depending on your class environment you may or may not want students to interrupt each other. The upside of interrupting it it could allow discussions to build and flow naturally. The downside is if you have a lot of quite students that don’t feel comfortable interrupting, you won’t have a wealth of ideas or participants in discussions.

For these reasons Hollander’s technique of deciding as a collective how discussions should be lead is useful.

Another useful technique we covered is questioning skills. We all use questions to start discussions, but not all questions are created equal. Some questions by their very nature promote discussion while others have such straight-forward, narrow answers that discussion is halted quickly. In our workshop we identified open vs. closed questions and quickly went over Bloom’s Taxonomy/Hierarchy of Questions.

We then discussed types of questions that dampen discussion (see below). Of the questions that dampen discussion, only the put-down and ego-stroking questions are questions that should never be used.

Closed questions along with low-level and programed answer question are essentially memory and knowledge questions that have narrow and straight-forward answers, which are hard to build a discussion off of. They aren’t the best for discussion, but they are great for reviews or summaries to evaluate if the class is understanding the material before you move on to a new topic.

Fuzzy questions can be hard to identify before you ask the question. But once said you can judge by the perplexed looks on your student’s faces that the question was unclear and follow up with another question.

Rhetorical questions can be great to emphasis a point, but when used during discussion they can confused students about whether they should reply to real questions.

Being comfortable with a longer wait times is best way to counter act rhetorical question confusion. Tips to help with wait time are to run through the alphabet in your head, count to ten, or my favorite - pull out a candy bar or banana and slowly unwrap it and eat it while you wait. One participant pointed out that Dorothy Leeds has written books on questioning, specifically “Seven Powers of Questions:Secrets to Successful Communication in Life and at Work” (first published in 2000).

We also talked about different discussion techniques. We specifically tried a Round-Robin exercise to practice our listening (and memory) skills. We asked participants to break in to small groups and state one thing they did that weekend. Then everyone in the group wrote what everyone else in the group did. This helped to illustrate that discussion is more than just speaking, it’s also LISTENING, THINKING, AND RESPONDING to those around you.

We also used a Town Hall and Post-It note structure as suggested by Chad Hanson (the full article can be found here). Hanson noted that by using this technique he was able to grade on participation, encourage quite students to speak up, and subtly remind more dominate speakers to give others a chance to speak. We had a chance to test out this structure by passing out two post-its at the beginning of the workshop and asking participants to stick one on their shirts when they spoke during whole group discussions.

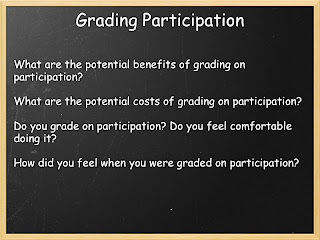

Initially we did not tell participants why they were doing this. But when we introduced this structure we explored how participants felt about advertising their participation and how they would feel if they knew they were being graded on the use of the post-its. This lead to a more general discussion of grading on participation.

Some of the costs of grading participation based only on speaking is that it puts quite students at a disadvantage and may affect the quality of discussion. However, setting the tone and having clear expectations may alleviate some of these concerns.

After giving our participants a chance to discuss in small groups different difficult scenarios they may encounter in their discussion sections, we reminding participants of Hollander’s use of collectively defining discussion.

We noting that she also asked students to reflect on their participation at the beginning of the course and either in the middle or end of the course. This reflection would help them define (at the beginning), improve (middle), and evaluate (middle and end) their discussion.

We ended by asked them to reflect on their participation in the workshop series.

thanks for posting the workshop notes. I found particularly useful the section on questioning skills. Also, reading about what type of interactive activities you used in the workshop give me good ideas on how to use them in other classes.

ReplyDeleteFirst, thank you very much for taking the time to post this material. These postings have been indispensable in synthesizing hand written notes into a coherent document. The worksheet handed out is well structured and insightful. Perhaps the following book might serve as inspiration to learn how to facilitate learning through inquiry:

ReplyDeleteThe Seven Powers of Questions by Dorothy Leeds:

http://www.amazon.com/Powers-Questions-Secrets-Successful-Communication/dp/0399526145

From a pedagogical standpoint, the sections on Stimulating Thinking and Getting Others to open up have been helpful in class! What a treat to have access to new resources!!!

@ Betta, I'm glad the post was helpful to people who weren't able to attend. I also learned a lot about improving discussions while developing this workshop with Sarah Augusto!

ReplyDelete@Andersson, please let us know if you see a noticeable difference in your discussions as a result of this workshop!